Marathon Man is a subversive, incredibly twisty, international espionage film written by William Goldman (from his own novel) and directed by John Schlesinger.

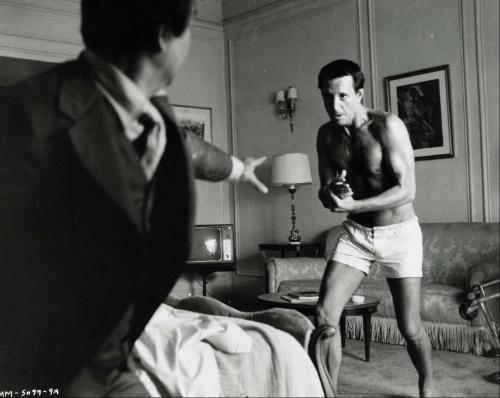

The film sets up an anonymous U.S. intelligence service against a Nazi war criminal hell-bent on moving hot diamonds across the world. Into the middle of the quagmire is dropped an innocent-but-paranoid graduate student and compulsive runner played by Dustin Hoffman.

Marathon Man came out ten years after Hoffman’s explosively star-making role in The Graduate. In the Graduate, he was cool as a cucumber, with a slight neurotic edge on the inside that was only barely visible to the audience. But by the time Marathon Man reached movie theaters, Hoffman had begun to perfect the obsessive-compulsive, nervous portrayal that would define many of his characters for years to come. There’s something about the era that encouraged this type of acting and tone to take root. It was also manifested in actors such as Woody Allen, and more modernly emulated by a talents such as Shia LaBeouf and Jesse Eisenberg.

It goes without saying that one of the aspects that makes Marathon Man a great paranoid thriller is the attitude and tone of Hoffman’s character, “Babe” Levy. In the beginning of the film, Babe is completely unaware of the grand machinations that are already happening around him and about to affect him directly. However, what’s fascinating is that even before Babe knows why he should be, he’s still paranoid. In that way, he represented the zeitgeist of the time (which is none too different from the zeitgeist of now, but perhaps with different evils).

The paranoid thrillers of the seventies were unique in that they began to expose a reality in which worldwide conspiracies were sophisticated, omnipresent and real.

In my opinion, the espionage capabilities that the United States and other nation-states had begun to develop during World War II were not truly exposed until the sixties came along. This related both to grand ambitions and to on-the-ground spy tactics. In the fifties, the general public knew nothing about poison umbrellas, dead drops, or the Illuminati. But as the Pentagon Papers were released in 1971, along with Watergate in the early-to-mid 70s, the American public became quickly attuned to what their own government was actually doing.

This dynamic mixed with the unstoppable rise in international business relations. It was during the sixties and seventies that white men in suits were beginning to show up in the capital cities of nations where they had not been seen in the past.

Hoffman, therefore, portrays a man who has almost been driven insane by the nature of the world around him. He is the everyman, our everyman, us, feeling as though the schemes of the world elite may collapse around us at any moment.

In an excellent side-plot, Babe is also dealing with a city (Manhattan) experiencing urban malaise. This is manifested in the petty criminals who live across the street from Hoffman’s character.

One of my favorite scenes involves Babe’s neighbors, who have harassed him throughout the movie. They think his running is weird, and they make it clear that they will rob him if they want to. For that matter, they make it clear that they’ll rob anyone. But when Babe needs them to get something from his apartment, knowing he’s being watched, the scene plays out hilariously.

I love the dialogue when Babe convinces his neighbor to help:

“What’s the catch?”

“The catch is… It’s dangerous.”

“That ain’t the catch. It’s the fun.”

Beyond that, the scene plays out hilariously when one of the agents from the “Division,” the secret intelligence agency represented in the movie, is rebuffed by two handfuls of thugs holding guns. It’s a classic example David vs. Goliath, showing that being a sinister secret agent only goes so far.

Here’s the clip:

“Syuzhet” vs. “Fabula”

In film school, we learned the difference between the “fabula” and the “syuzhet.” The former is what actually happened, whereas the latter is “how it is shown.” Marathon Man is not a simple movie to understand. It is easier to figure out the fabula by reading the summary on Wikipedia. That’s because the scenes that play out on the screen, and the manner in which information is dispensed, can be confusing.

The positive is that holding the entire plot in one’s head doesn’t completely matter. Much of the movie is, just like Hoffman’s character, about tone. The exact plot is less important than the viewer sitting on the edge of their seat, their own mind being ripped to shreds by the anxiety displayed onscreen.

But the movie also remains exciting. The bad guy, Szell, played by Laurence Olivier, is excellent. His altercation with Hoffman at the end of the film is remarkable and memorable. I will leave you with this passage, pulled from the original New York Times review of the film:

“If you were forced at gunpoint to swallow at $16,000 diamond, what would you do? Stall for time by asking for a glass of water? Say you were allergic? Cry? It’s not a problem most of us are likely to face. It would seem to be too special to engage our interest at gut level. It’s like worrying about what to do with a case of empty Dom Perignon bottles.

Yet when Laurence Olivier, who plays a sadistic ex-Nazi war criminal in “Marathon Man,” confronts such a situation, it becomes a matter of universal concern and immense wit in spite of the desperate circumstances.”

I couldn’t put it any better.

You’ll have to watch Marathon Man, all the way to the end, to see what happens.